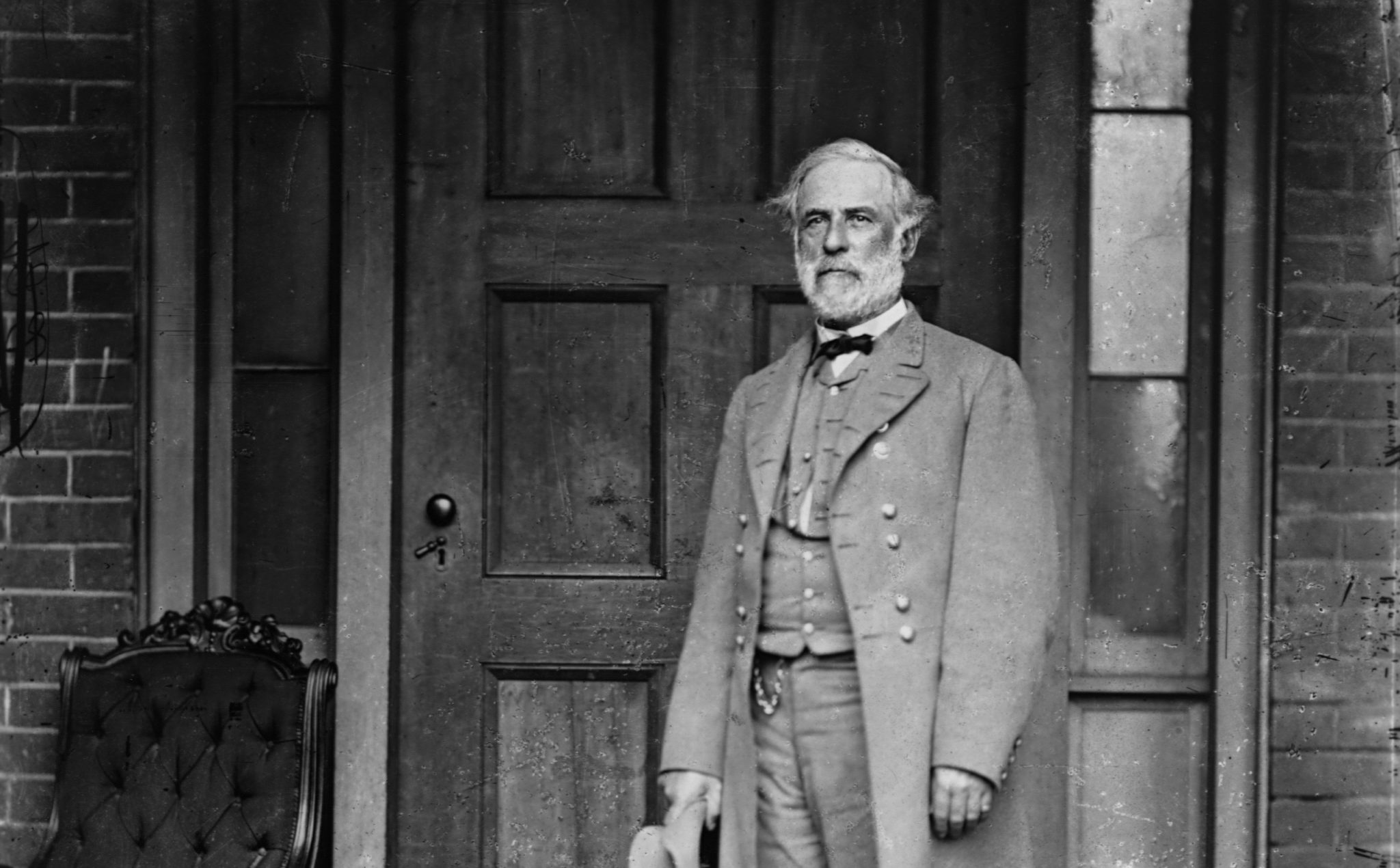

By JAMES G. WILES || What made Robert E. Lee great was that he accepted defeat. At (and after) Appomattox, Lee repeatedly turned away any suggestions from Confederate “dead-enders” that he should lead his Army of Northern Virginia into the Blue Ridge mountains to launch a guerrilla war.

The Spanish had done it against the French in the Peninsular War. Why should not the defeated Confederacy?

Lee said no. At (and after) Appomattox, Lee decided that he loved his country more than the cause he had fought for. The “red-faced Lees” had been present at the birth of the American Republic. Defeated, Lee would re-join that Republic again – although he never applied for a pardon restoring his civil rights.

One might say, therefore, that the former U.S. Army officer who had broken his oath also accepted his country’s punishment.

What made such a strong character possible was that Robert E. Lee was both a soldier and a believing Christian – an Episcopalian, to be exact. Lee did not find his religious faith inconsistent with his profession as a soldier, a profession which required Lee to kill his fellow man. The way Lee reconciled this was through his soldier’s Old Testament belief that, whatever the failings and misperceptions of fallen humanity, God gave the victory to the side whose cause was righteous.

President Abraham Lincoln, who was no kind of soldier, believed the same. In his Second Inaugural Address, his great meditation on the causes and meaning of the Civil War, Lincoln said this:

“Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully.

“The Almighty has His own purposes. ‘Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.’ If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always

ascribe to Him?

“Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said: “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

These are words of faith which, perhaps, today’s generations of Americans cannot speak – or cannot hear. Because they no longer believe.

But Robert E. Lee and Abraham Lincoln could – because they believed.

Lee the soldier believed that in April, 1865, God gave his verdict between the United States and the Confederacy. And, therefore, in his religious faith, Lee accepted that verdict. After Appomattox, there would be no guerrilla war, no Klan, no insurgency, no Redeemers for Robert E. Lee. That would come later – after Lee had died.

Instead, once again, Robert E. Lee – who had been commandant of West Point – would be a college president. He retired to become the president of what’s now Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. Lee supported President Andrew Johnson‘s version of Reconstruction and advocated sectional reconciliation.

And there, in Lexington, Robert E. Lee died in 1870. Few then remembered that the South (and perhaps America’s) greatest general had opposed secession. After Appomattox, he opposed Confederate war memorials and banned display of the Confederate flag on his campus. When he died, Lee was buried in his civilian clothes and Confederate veterans attending his funeral, like their general, wore mufti.

Robert E. Lee, by what he did at Appomattox and afterwards, made peace possible.

That is enough of a reason to keep Lee’s statues up – and shining. And to honor the lesson Lee taught us. It is also enough to make Robert E. Lee (whom my ancestors fought against) an American hero.

Like Ulysses S. Grant, his greatest opponent, Robert E. Lee’s greatest lesson is: “Let us have peace.”

James G. Wiles is a Republican consultant based in Myrtle Beach, S.C.

***

WANNA SOUND OFF?

Got something you’d like to say in response to one of our stories? Please feel free to submit your own guest column or letter to the editor via-email HERE. Got a tip for us? CLICK HERE. Got a technical question? CLICK HERE.

Banner via National Archives